Modeling the distribution of impact melts at the Apollo 14-17 landing sites

Introduction

Ever since the Apollo astronauts brought back hundreds of kilograms of rocks from the Moon, scientists have been interested in where on the Moon these rocks originally came from. Because impact cratering is the most important geological process to affect the surface of the Moon, most of these rocks were produced and transported by impacts. This is especially true for rocks collected from the Apollo 14-17 missions, which landed in regions that were not volcanic.

Out of all the samples associated with impacts, impact melts are the most important for my study. That is because the radiometric age of an impact melt should theoretically also be the age of the impact that produced the melt. This is not always true for other types of impact rocks. The goal of this modeling study is to determine which craters deposited significant amount of impact melt (and thus transported other, non-melt materials) at the Apollo sites.

Methods

For this project, I used a Monte Carlo impact bombardment model called the Cratered Terrain Evolution Model (CTEM). CTEM works by emplacing craters on a three-dimensional, square grid. In the past, all the craters CTEM emplaced were random. However, I added the ability to emplace specific craters at a given location and model time. I used this to emplace the 74 largest craters on the Moon (known as basins) in locations corresponding to their true location on the Moon, and with model times consistent with a model of the lunar cratering chronology. I also emplaced a few dozen “sub-basins” in the same manner. These craters are smaller than basins, but still very large craters; the largest of which (Iridum) is ~250 km in diameter!

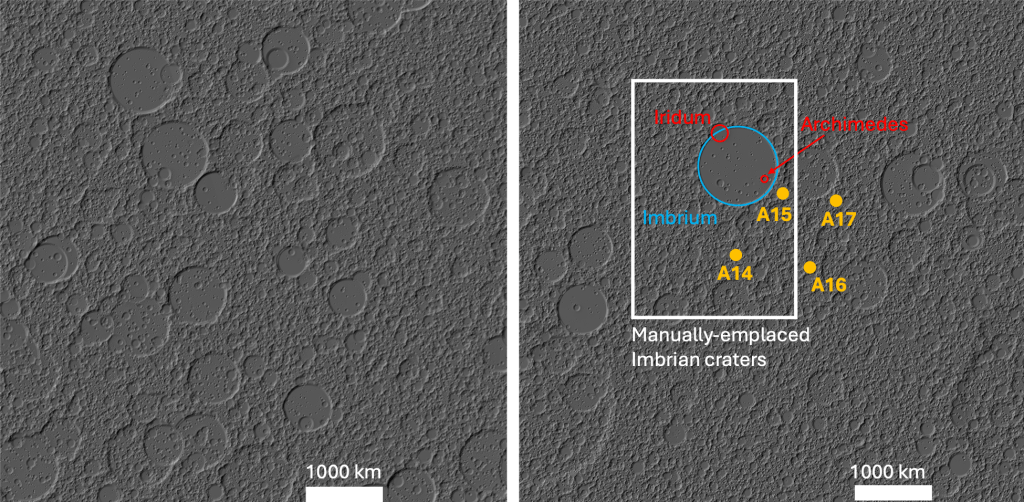

The image on the left is what a normal CTEM simulation looks like, and the image on the right is one of my simulations. The emplacement of large basins like Imbrium allows the simulated surface to resemble that of the actual Moon. I can then track the source craters of impact melt at pixels corresponding to the Apollo 14-17 landing sites. For this study, I focused on the Imbrian period, which took place between 3 and 3.9 billion years ago.

One of the strengths of CTEM is its crater ray model. In the past, CTEM modeled distal ejecta (ejecta >~3 crater radii) as homogeneous. However, real distal ejecta follows heterogeneous patterns known as crater rays. I have calibrated the crater ray model of CTEM based on literature studies of secondary craters (which are associated with rays). Thus, the material transported as distal ejecta should be more accurate than before!

Results

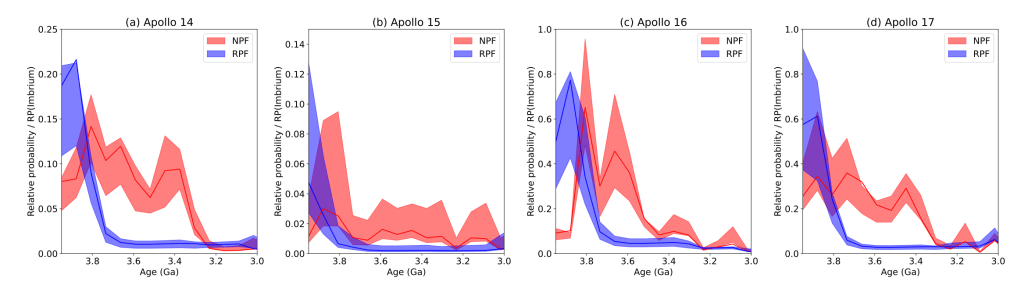

There are two separate models for the rate of impactors during the Imbrian Period. The classical model is the Neukum Production Function (NPF), and a newer model is the Robbins Production Function (RPF). The rate of impacts declined much more rapidly under the RPF than the NPF. I modeled the impact bombardment of the Moon under each production function, and the result for the Apollo 14-17 sites is below:

These results show that under the NPF, there is more impact melt with Late Imbrian ages (<3.7 billion years). This makes sense because melt under the RPF would be older due to the rapid decline in impact bombardment. But how does this compare to the age distribution of Apollo impact melts? We scaled our model results to the number of Imbrian-aged impact melts collected at each Apollo site. Our results are shown below:

The above image shows that our model results under the RPF are a closer match to the age distribution of Imbrian Apollo impact melts than our results under the NPF! This means that the ages of Apollo impact melts support a rapid decline in impact bombardment during the Imbrian period as predicted by the RPF! Note that this does not mean the impact rate exactly followed the RPF– just that there was likely a steep decline in impact rate during the Imbrian.

Our paper has been published at JGR:Planets!

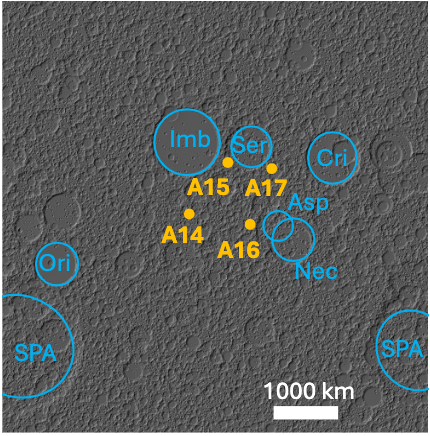

This research is applicable to more than just the Imbrian! The largest craters on the Moon are known as basins, and they were emplaced by impacts early in lunar history. We can use CTEM to model the amount of melt each basin contributes to each studied Apollo site. The image below shows the locations of several prominent basins, as well as the Apollo landing sites, on the model grid.

There are many different combinations of craters that could transport melt to the Apollo sites. As this is a Monte Carlo simulation, it was run numerous times and the results were aggregated. Once the numerical model was done, we developed a technique based on Bayesian statistics to identify which basins were the likeliest to contribute to Apollo samples.

Asperitatis

The image above shows the basins most likely to be the source of a 4.29 billion year old Apollo 16 sample. The likeliest basin is Asperitatis (Asp in the above figures). Asperitatis is so heavily degraded that it wasn’t discovered until 2015. That is because you can only see it with gravity data. However, it is closer to the Apollo 16 landing site than even Nectaris! So, it must have deposited a lot of melt at the Apollo 16 site very early in lunar history. If any of that melt survived to the present day, it could have been returned by the Apollo astronauts!

Potential Scenarios

The Imbrium basin is known to have impacted 3.9 billion years ago, but it is one of the youngest basins on the Moon. The older basins do not have confirmed ages, largely due to the difficulties in correlating samples to basins (which is what we are trying to model!) There is, however, evidence that the Serenitatis basin impacted at 4.2 billion years ago. Our Bayesian analysis also indicates that Serenitatis has a high likelihood of sourcing samples with that age. So, if we take Serenitatis to be 4.2 billion years old, we can construct scenarios based on the basins with ages in between Imbrium and Serenitatis. The two basins most likely to contribute are Nectaris and Crisium.

If we correlate Crisium to a group of samples 3.95 billion years old and Nectaris to a group ~4 billion years old, we get a spike in impact rate at this time similar to the concept of a “late heavy bombardment”. If Crisium is the source of the 4 billion year old samples and Nectaris is the source of a group that is 4.1 billion years old, the impact rate would have followed a smooth decline. We can also get a hybrid of these two, if Crisium is the source of the 3.95 billion year old group and Nectaris is the source of the 4.1 billion year old group. While it is not possible to know for sure which basin sourced which group (some samples may not have come from basins at all), this is still useful because the NPF model age of Serenitatis is 4.2 billion years, which is what its true age is believed to be. Even if Serenitatis is 4.2 billion years old, that does not necessarily mean that the impact rate followed the NPF until that time!

Our paper is published at JGR:Planets!